Read some of our Latest articles.

Read some of our Latest articles.

There is a legend that Gordius, founder of Phrygia, lashed his chariot (or was it an ox-cart?) to a pole with a knot so intricate that only a man great enough to conquer all Asia would be able to untangle it. In 333 B.C. (the story goes) Alexander the Great solved the problem of the Gordian knot by slicing it in half with his battle sword. Since then a “Gordian knot” has become synonymous with any intractable problem. Alexander’s solution has become an advertisement for swift, decisive action.

Phrygia possessed just one Gordian knot. We Americans seem to be in possession of a barrel-full. The issues of race, class, inequity, due process, immigration, law and order, rampant crime, and corruption seem to become more complicated with time. Police shootings (by which I mean police shooting civilians, and civilians shooting police) may once have been under-reported. They are not under-reported now, and the mayhem produced seems to grow exponentially.

I recently reread Larry McMurtry’s book on massacres in the American West*. Some of those mass killings were the result of evil plans carried out by evil men – the Mountain Meadows Massacre for instance, or the Massacre of the Blackfeet at Marais River. Some were led by unrepentant racists – like Major Chivington’s massacre of peace Indians at Sand Creek, or John C. Fremont’s massacre of Maidu at the Sacramento River. Some massacres - the Fetterman massacre and the Little Bighorn - were the result of a toxic brew of hubris and stupidity. Most of the massacres, and the worst of them (Washita and Wounded Knee) were caused by fear.

Young men, frightened, a thousand miles or more from home, cold, tired, stressed, often acting on false information surround a village of Sioux, or Cheyenne, or Paiute and during a tense standoff something happens – a horse bolts, or a gun goes off and then everything explodes into violence. When the smoke clears the bodies of women, children, and the aged litter the prairie.

Fear was the cause of the majority of, and the worst of the massacres in the American West. The fear itself was reasonable. Many of the Plains Indians were formidable, often merciless enemies. But much of the time reasonable fear produced unreasonable acts.

In the July 13th Washington Post there was a story covering the much-discussed study by economist Roland Fryer, of fatal shootings by police. He found, much to his own surprise, that although racism played a role in many of the shootings, fear was the primary culprit. In high crime neighborhoods officers were quick to draw a weapon, and quick to feel threatened. These two responses to a reasonable fear made unreasonable force seem perfectly reasonable in the moment. This finding seems to describe a problem even more intractable. Racism is never reasonable, but fear often is.

If the issue is fear, we Christians alone have a response. There is no fear in love. Perfect love casts out fear because fear involves punishment. The one who fears is not perfected in love (I John 4.18). I didn’t say we Christians have an answer – only a response – we still live in a sinful, decaying world (I John 2.17). But when we love selflessly, when we are involved in our communities as loving Christians (instead of griping about them and cocooning ourselves), we plant seeds that will bear fruit (James 3.13-18). This is the only response that will mitigate the level of fear which has tied this knot. Maybe then our communities will not demand more of our officers that they ought.

Love requires a significant investment of resources, energy, and time. We prefer Alexander’s strategy – we prefer to hack through a problem in one irritated stroke. Most problems are not so easily solved.

The earliest version of the Gordian knot story has Alexander cutting into the knot in order to find the ends, so he could begin the intricate job of untying it. This is more like real life. This is something we can do – especially since love provides the knife with which to begin.

*Oh What a Slaughter, Larry McMurtry, Simon & Schuster, 2005.

I need to share with you the fourth worst thing I have ever done – at least by my own reckoning it is the fourth worst. The three worst things I have done (by my reckoning) I will keep between God and me. When I was a sophomore at OVC, I was scheduled to lead the last dorm devo of the year. We had a guy in our dorm who had started to smell funny. It wasn’t because he needed a bath, he was quite fastidious. It wasn’t that he smelled particularly bad – just funny, like a dog after a bath. Somebody told him he needed sheep dip, and we all thought that was hilarious. Someone else went to Southern States and bought him some sheep dip. Others of us used to go “bah” whenever he walked by.

So I planned a devotional around the theme of sheep – of Jesus as good shepherd, of the church as the flock. We sang “Fear Not Little Flock,” “The Lord My Shepherd Is,” and “The Ninety and Nine.” Everyone had a high old time. This was the fourth worst thing I have ever done. It was disrespectful to the Word, blasphemous toward God, and hateful to the brunt of our joke – and it gives you a notion of how bad the other three are.

Shortly after the farcical devotional ended a fellow-student came to me, fighting back tears, and asking for prayers. The Devotional had really touched his heart, he needed to repent, and wanted me to pray with him. I have done worse things, but have never been more ashamed. The moment was about him, though, and so I did pray with him – sincerely and earnestly – all the while knowing I did not deserve to be heard. I don’t know I am a much better man now, but I have never intentionally disrespected the Word since.

I learned something important about the Word that evening – something I will always remember. The Word accomplishes its own work. I had made a joke of it, but it is stronger than any mockery we can level. The light shone through despite me. The Word has its own work. It is living and active, sharper than a two-edged sword, able to divide bone from marrow, and discern between soul and spirit (Hebrews 4.12).

It would be years, though, before I would learn not to interfere with the Word’s own work. As long as I have been preaching folks have come to me, telling me how the sermon spoke directly to them – only to mention a point I had not made at all. I found this very discouraging. Sometimes I blamed my listeners for doing a poor job of listening. Most often I blamed myself for being a poor communicator. Only later, only gradually did I realize that this was just the Word having its own work.

The Word is alive and active. I believe this. Thus I must believe that it has power beyond my feeble attempts at communication. If this is true then someone receiving a comfort or insight from a sermon which I really didn’t intend to give is evidence that the Word is at work. Thus, my job is to present the word simply - without pontificating or persiflage. When the word is shared thus, it will have effects a preacher never imagines. I now believe these unintended consequences are evidence I have done my job.

There is an old preacher’s illustration comparing a stained glass window to an open one. A stained glass window may be breathtakingly beautiful, but an open window lets in the pure light of the sun. We think we have to string together humorous and heartwarming anecdotes on the way to sharing 10 Points to a Better You. That may be entertaining, even inspiring – but it’s all just stained glass. Anyone who stands before the gathered family of God has one task – to open the window and let pure light stream in. When that happens there will be all sorts of unintended and unimagined consequences – at least from our perspective. But God will see things proceeding just as He intends.

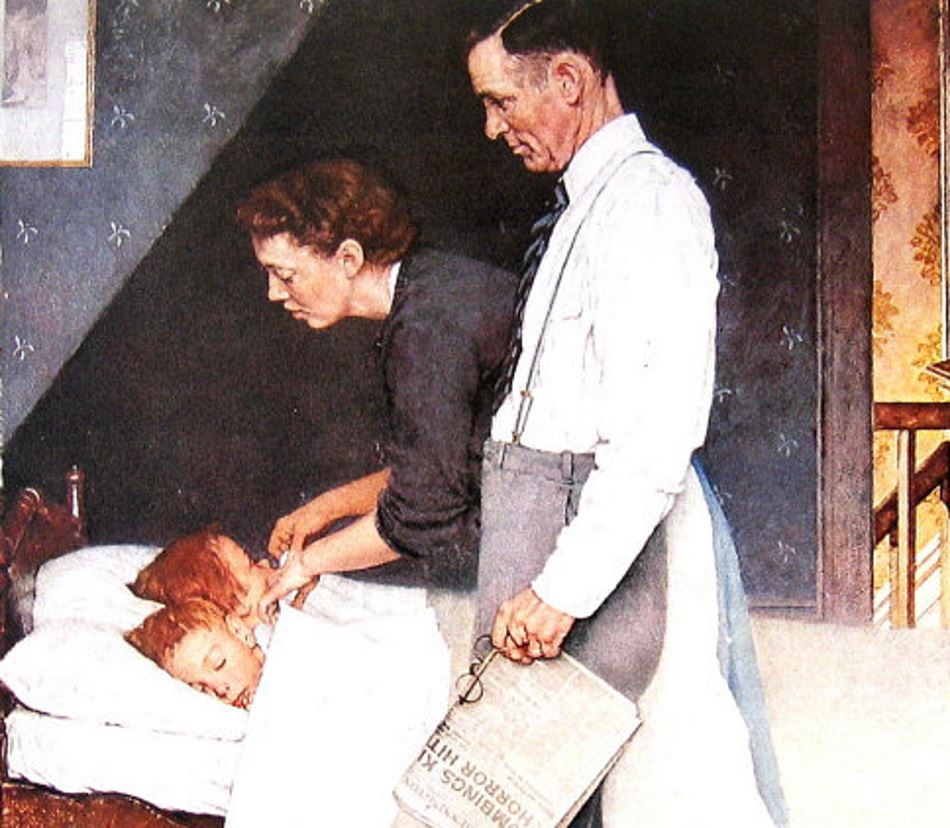

There are no painters more closely associated with Americana than Norman Rockwell, and Grant Wood. Rockwell’s covers for Look, and The Saturday Evening Post, as well as his illustrations are the images in our collective memory. When we remember Rosie the Riveter, and Ruby Bridges we remember his paintings of them. Grant Wood’s “American Gothic” is, undoubtedly, the most recognizable image in American art. Both men also share the experience of being tossed on the heap of the irrelevant and maudlin, only to be reconsidered by later generations for the darkness in their work that had somehow been missed.

Wood is a satirist, and Rockwell a journalist, but both men had serious critiques to make about American society. In Wood’s hilarious and unsettling “Parson Weems Fable,” he portrays the popular and completely fabricated story of George Washington chopping down the cherry tree. It is blunt-force irony that a story about truth-telling is a lie, and so he paints the story as happening on a stage behind a theatrical curtain. In the painting, little George has the body of a 6-year-old, but the face of the Gilbert Stuart painting on the one-dollar bill. In the background slaves are picking cherries – exposing an even larger lie than Parson Weems’ fib about George’s little hatchet.

In Norman Rockwell’s painting “Freedom from Fear,” part of “The Four Freedoms” series inspired by a Franklin Delano Roosevelt speech, Rockwell paints a couple putting their children to bed. They are a boy and girl, maybe 5 and 7 years old. Mom is tucking in the blanket, and dad is quietly looking down at the kids. The series, painted in 1943, was a vivid reminder of the blessings of being a free people, of why we were fighting. The thing is - the painting is filled with fear. To be a parent is to be afraid for your children, and those fears are clearly on the dad’s face. No wonder – in his hand is a newspaper whose headlines read: “Bombings Kill…./Horror Hits….” On the ground a grey-striped pajama top reminds one of the uniforms Jews wore in the death camps. Even a doll lies on the floor like a corpse. There is no freedom from fear.

Both paintings juxtapose the way things ought to be with the way they are as a protest to their incongruity. That’s fine. We should always take a hard look at the way things are, and strive to make things the way they ought to be. We should never be satisfied with coming up short.

The problem is that we often blame God for this incongruity. The fault is ours. God didn’t invent lying, slavery, or genocide. We did. God makes things the way they are supposed to be. We sin and make them the way they are. When I was a young man preparing myself for ministry I knew I would have to defend the faith (the doctrines of the New Testament), and faith (the existence of God), but I had no inkling that more often than either of these defenses, I would be challenged about the goodness of God.

My only assertion in this little piece is that God is good, and that the way things always fall short of how they ought to be is about us, not about Him. God makes things the way they are supposed to be. We make them the way they are.

Oh taste and see that the LORD is good! Blessed is the man who takes refuge in Him. Psalm 34.8 ESV

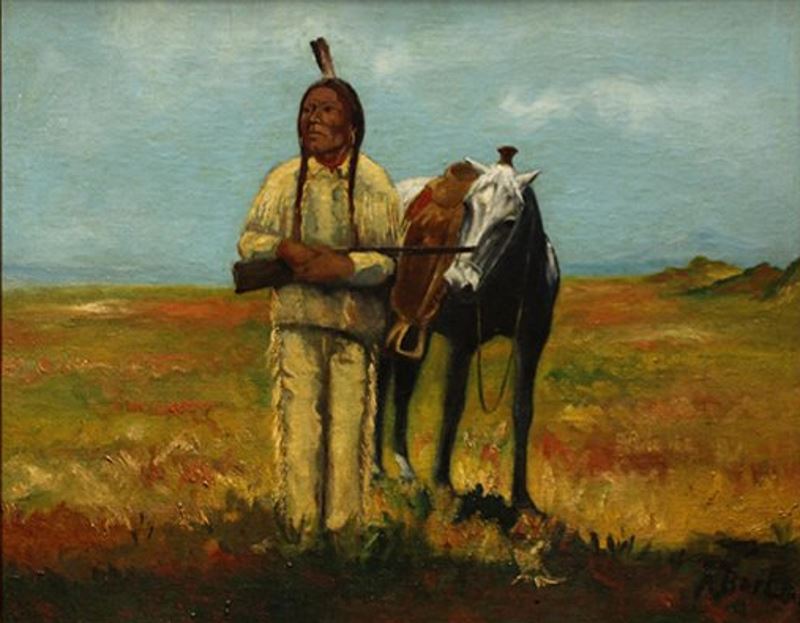

When George Armstrong Custer led 700 men of the 7th Cavalry against the great village of Plains Indians on July 25, 1876, he was planning a massacre. He got one – but not the one he was planning. Despite the fact that his men were exhausted from a prolonged pursuit, upon locating Sitting Bull’s village by the Little Bighorn River, he ordered Major Marcus Reno to pursue 40 Lakota warriors they stumbled upon, and attack immediately from the south. Custer promised he would follow and reinforce them, but immediately moved north.

Reno’s men did not charge the village, but dismounted within range of it and established a firing line. The village was momentarily thrown into confusion as warriors organized themselves for its defense. Sitting Bull sent his nephew and another warrior out under a white flag to ask Reno to negotiate. Reno’s men shot and killed them both. Sitting Bull was mounted on his favorite horse, deciding what to do next when his horse was shot and killed beneath him. This was the trip-wire. He cried, “They have killed my favorite horse. It is like they shot me. Attack them!” Reno’s men were quickly forced to mount and flee back to the bluffs, and the safety of Major Benteen’s force. They could already hear the gunfire Custer’s men were exchanging with the Sioux and Cheyenne.

A good-sized public library would be needed to hold all the books written about Custer’s defeat that day. Custer was lionized for half a century as the embodiment of honor and bravery. He is now generally regarded as a blow-hard, a philanderer, and a narcissist of the first order who wasted the lives of soldiers and Indians for his own personal glory. As a reader, I find him hardly worth my time. I am much more interested in Sitting Bull.

I am interested in the fact that he finally got angry when they shot his horse. He took the shooting of his nephew calmly, but the killing of his favorite horse he took personally – as he said “It is like they shot me.” We all have our limits.

Our personal limit - that trip-wire which shatters patience and incites anger - communicates something essential about us. It identifies what we really care about. Some of us care about ourselves, therefore any annoyance or slight can be a trip wire. Some of us will continually accept personal insult with patience, but let someone insult spouse, or child, or parent, or friend, or country, and we say with Sitting Bull “Attack them!” For some the trip wire is injustice generally, or against a certain group specifically. We each have trip-wires and they identify our core values.

The word “anger” is only used of Jesus only once, In Mark 3.5. Jesus is being baited by the Pharisees to see if He will heal on the Sabbath. There is a man at the Synagogue with a withered hand. No one there cares about this man – his pain, his hardships, his limitations – they are just waiting to pounce. Jesus asks them if it is lawful to good or harm on the Sabbath, to save a life or to kill, but they are silent. Then “looking around in anger, grieved at the hardness of their heart” Jesus heals the man.

One might also argue that when Jesus cleanses the temple (Matthew 21.12-17, Mark 11.15-19, Luke 19.45-48, John 2.13-22) he is expressing anger – that His trip-wire has been sprung. Maybe. Let us assume so. What do these two incidents tell us about Jesus?

They tell us that cruelty towards others and irreverence towards God produce in Him a visceral response. His anger is never aroused by any attack upon himself. He is certainly not a man who lashes out at inconvenience and annoyance. We allow ourselves such large latitude for angry response to both. The Bible reminds us that “the anger of man does not accomplish the righteousness of God” (James 1.20). We know from observing Jesus, anger is only righteous when one cares most about righteousness. To control our anger we must choose a worthy trip-wire – we must care most about God and others. Otherwise anger will not be controlled.

At my first job in Rome, Ohio there were two sisters I used to visit every week. Iva Callicoat and Edna Sowards lived together in Iva’s house just a few blocks from the church building, and I would walk over in the afternoon. They were a real-life Mary and Martha – Iva was practical and wise, Edna was quiet and wise. I learned so much from them. I was really blessed by my first work. I had five elders who were true shepherds, a pulpit minister who wanted (for the most part) to mentor me, and a loving congregation which treasured my wife and me. It was an idyllic situation, and a rare one – especially for the Ohio Valley which is notorious for congregational strife. My home church seemed always to be arguing about something, and split while I was in college. In fact, two generations ago our entire sisterhood of congregations seemed to have that reputation. Members of the churches of Christ seemed always ready to give an answer (or at least engage in debate) but with no gentleness, and little reverence (see I Peter 3.15).

We weren’t like that at the Rome Church of Christ. There were points of controversy now and then, and a few persistent scriptural disagreements, but none that disrupted family harmony. It was amazing to me that a church family could be that way. What we did have at Rome was a long prayer list. Although a large congregation for the area (we averaged around 325 on Sunday mornings) it was an aging congregation. We averaged 15 funerals a year during my time there. It was not unusual to spend three full days visiting hospitals during a work week.

I was commenting on this to Iva and Edna one summer afternoon. I was bemoaning (complaining is probably a more accurate word) the fact that so many were ill and so many had died. “I guess I should be thankful we aren’t fighting amongst ourselves the way most churches are. We just have so many to worry about,” I remarked. “That’s why,” Edna replied. I didn’t understand. “That’s why what?” I asked. “We are so busy worrying and caring for each other that we don’t have time to fight. That’s why,” she explained. Of course, of course, that was indeed why.

I remembered her words this week as I watched the folks who live around Baton Rouge take care of each other. Just a few weeks ago Louisiana was wracked by racial tension. Police shootings, the candidacy of David Dukes, and the presidential campaign seemed to be splitting the state wide open along racial lines. After the Storm-With-No-Name dumped more water on the state than did Hurricane Katrina the citizens of Louisiana now (for a time) seem to identify themselves not as black and white, but as wet.

I have often quoted Fred Rodgers’ advice to children, given in the wake of 9-11 – to “look for the helpers” in any disaster, because they are always there. His words remind us of the truth of the beatitudes. They who mourn are blessed, because they will be comforted.

The challenges we face we have created ourselves. God gave us a garden home, each other, and a perfect relationship with Him. We have ruined it all. We have fouled our planet, fought each other, and forsaken God. He has not forsaken us. What a blessing God has given us – that in the face of the gravest challenges we find the greatest gifts – unity, benevolence, altruism, selflessness, brotherhood, love.

The greatest gift we receive in crisis is experiencing of God’s goodness in the goodness of others. We experience this gift more purely in the wake of crisis, than at any other time. How wonderful that God has arranged for this to be so even in this sinful world we have made. Thanks be to Him in all things.